THIS CONTENT REFLECTS THE PHILOSOPHY OF BOYLEDOWN LENDING INC., A CONSUMER FINANCE COMPANY LICENSED BY THE VIRGINIA STATE CORPORATION COMMISSION (LICENSE number CFI-256). IT IS INTENDED AS INFORMATIONAL CONTENT AND PROMOTES OUR LENDING MODEL. AS SUCH, IT IS CONSIDERED AN ADVERTISEMENT.

AI Disclosure:

This article was developed with the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) using OpenAI’s ChatGPT. While the ideas and editorial direction reflect the author’s perspective, portions of the research, structuring, and drafting were supported by AI-generated insights. All content was reviewed and finalized by the author.

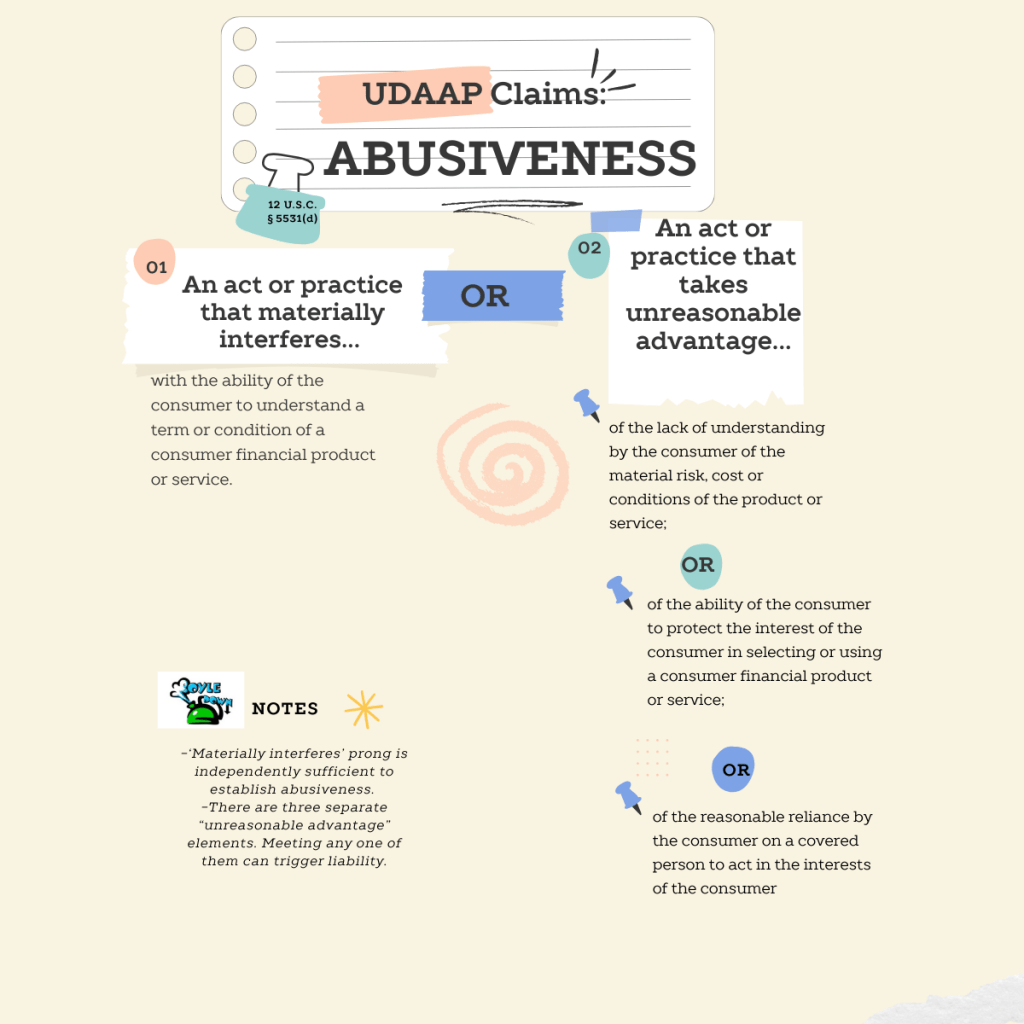

UDAAP Abusive Elements

Notice that unlike unfairness and deception, abusiveness claims are only valid if they are brought against entities subject to the Dodd-Frank Act.

Here’s the distinction, clearly laid out:

FTC UDAP (Unfair or Deceptive Acts or Practices)

- Governed by FTC Act §5.

- Applies to most businesses except banks, credit unions, insurance companies, common carriers, and certain nonprofits.

- Standard: Only unfairness and deception.

- No “abusiveness” prong — the FTC does not have abusiveness authority.

CFPB UDAAP (Unfair, Deceptive, or Abusive Acts or Practices)

- Created under Dodd–Frank Act, 12 U.S.C. § 5531 & § 5536.

- Applies to “covered persons” in consumer financial products and services (e.g., lenders, servicers, brokers, debt collectors, payment processors).

- Standard: unfairness, deception, plus abusiveness.

- Abusiveness is the “extra” element Congress gave CFPB authority over that the FTC does not have.

📌 Bottom line:

- If you’re dealing with consumer finance (CFPB jurisdiction) → all three prongs (UDAAP) apply.

- If you’re under general commerce/business practices (FTC jurisdiction) → only unfairness and deception (UDAP).

The Abusiveness Standard — Where It Stands Today

Statutory Basis (always controlling)

Dodd–Frank Act, 12 U.S.C. § 5531(d) defines “abusive” practices. That text is still the only binding authority — regardless of what policy statements say.

Elements:

–Materially interferes with a consumer’s ability to understand a term or condition of a product/service; (Meeting this is independently sufficient to raise a valid abusiveness claim under the ‘material interference’ prong)

OR

–Take unreasonable advantage of

-A consumer’s lack of understanding of material risks/costs/conditions; OR

-A consumer’s inability to protect their interests in selecting/using a product; OR

-A consumer’s reasonable reliance on a covered entity to act in their interests

(Each of these is an independent trigger — meeting any one is enough to raise a valid abusiveness claim under the ‘unreasonable advantage’ prong.)

Policy Guidance- History, Developments and Current State

- CFPB 2020 “Abusiveness Policy Statement” (under Trump/Kraninger):

- Said the Bureau would enforce “abusiveness” cautiously and avoid “dual pleading” with unfairness/deception.

- Tried to narrow practical enforcement.

- 2021 Rescission by CFPB (under Biden/Chopra):

- CFPB rescinded that 2020 statement.

- Reason: the guidance was seen as creating “unwarranted limitations” on CFPB’s statutory authority.

- Result: back to full statutory text in Dodd-Frank — no “softened” enforcement stance.

Current State (2025)

- There is no binding policy guidance limiting “abusiveness.”

- CFPB (under Chopra) has said it will use the statutory definition as written.

- That means the abusiveness standard is broad and flexible, and companies should assume CFPB has full discretion to apply it.

✅ The rescission means all you can truly rely on is the statute’s language itself (12 U.S.C. § 5531(d)), along with how courts interpret it in enforcement cases.

How have courts interpreted the abusiveness standard in enforcement cases since rescission?

- After rescinding the 2020 Trump-era policy that discouraged standalone abusiveness claims, the CFPB under the Biden Administration reaffirmed its commitment to enforcing abusiveness strictly based on statute, citing supervisory and enforcement discretion Alston & Bird

- In 2023, the CFPB released a Policy Statement reestablishing that abusiveness could be enforced independently, clarity now supported by legal continuity Federal Register ; Morgan Lewis.

- As of now, no publicly accessible enforcement case documents specifically assert abusiveness as the sole basis for liability; almost all CFPB actions still pair abusiveness with unfair or deceptive claims Mayer Brown. There is no recent example where abusiveness alone was pleaded or litigated in the public record.

While the statute allows for standalone abusiveness claims, in practice the CFPB continues to largely rely on combined UDAAP allegations. The trend shows a preference to assert abusiveness alongside unfairness or deception rather than in isolation.

Why Did Congress add the “Abusiveness” language in the Dodd-Frank Act (2010) Instead of just copying the FTC Act’s “unfair or deceptive acts or practices” (UDAP) language?

Here’s the breakdown:

1. Unfairness (FTC & CFPB)

- Standard: Causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers that is not reasonably avoidable and not outweighed by benefits.

- Focus: Balancing test, looks at harm and avoidability.

- Classic cases: Hidden fees, unsafe products, predatory terms when consumers couldn’t reasonably protect themselves.

2. Deception (FTC & CFPB)

- Standard: Misrepresentation or omission likely to mislead a reasonable consumer, material to their decision.

- Focus: Truthfulness and accuracy of information.

- Classic cases: False advertising, misleading disclosures.

3. Abusiveness (CFPB only, 12 U.S.C. § 5531(d))

- New element: Goes beyond unfairness/deception by focusing on the relationship and relative power between a company and consumer.

- Prohibited when it either:

- Materially interferes with a consumer’s ability to understand a term or condition of a product or service;

- Takes unreasonable advantage of:

- a lack of consumer understanding of material risks, costs, or conditions;

- consumers’ inability to protect their own interests in selecting or using a product; or

- consumers’ reasonable reliance on a covered person to act in their interests.

- Key difference: It doesn’t require proof of deception (lying/misleading) or the unfairness balancing test.

Instead, it can capture practices where the consumer is over-reliant, confused, or structurally disadvantaged even if the company gave technically accurate disclosures or no “substantial injury” is proven.

What this means in practice

- FTC-covered entities (banks exempt, nonbanks outside CFPB scope):

They only face unfairness and deception. They don’t have to worry about claims like:- “You didn’t mislead, but you knew consumers didn’t understand and you exploited that.”

- “You structured a product that the average consumer could not realistically evaluate.”

- “You allowed reliance on your advice that wasn’t in the consumer’s best interest.”

- CFPB-covered entities (banks, certain lenders, certain financial service providers):

They must worry about “taking unreasonable advantage” of consumer vulnerabilities even absent deception or harm balancing.

✅ In theory: Abusiveness is about exploitation of consumer weakness or trust.

❌ What FTC entities don’t face: Liability where disclosures are technically clear, harm isn’t substantial, but regulators believe the firm still took advantage of asymmetry in knowledge or reliance.

Examples of What Could be Abusive Under CFPB UDAAP Statute but Not Necessarily Unfair or Deceptive under FTC UDAP Statute Which Does not Have an Abusiveness Provision.

1. Reliance Exploitation

- Scenario: A payday lender markets itself as a “financial advisor” and builds long-term relationships in small towns. It doesn’t lie (no deception), and loans are disclosed clearly (no interference). But consumers reasonably rely on the lender’s advice to “roll over” loans, thinking it’s in their best interest.

- Why it’s abusive: CFPB could say the lender took unreasonable advantage of reliance.

- Why it’s not unfair/deceptive: No false statement, no hidden harm — disclosures are accurate.

2. Knowledge Exploitation

- Scenario: A mortgage servicer designs a loan modification process so complex that most borrowers give up and accept foreclosure alternatives. Nothing false is said (not deception). The harm (loss of house) is clear, but servicer could argue foreclosure is “reasonably avoidable” since consumers could complete paperwork.

- Why it’s abusive: Consumers lack understanding of the system’s material risks and the servicer unreasonably benefits.

- Why it’s not unfair: Servicer can argue injury was avoidable if borrower “tried harder.”

3. Fine-Print Interference

- Scenario: A credit card issuer buries a mandatory arbitration clause in a long, confusing disclosure. It’s technically disclosed (not deception), and consumers could “avoid” harm by reading carefully (so maybe not unfair).

- Why it’s abusive: It materially interferes with ability to understand terms — average consumers can’t realistically grasp the effect of the clause.

- Why it’s not deceptive: The clause is there, not hidden.

- Why it’s not unfair: Harder to show “substantial injury” or that it wasn’t reasonably avoidable.

4. Asymmetry Exploitation

- Scenario: A fintech app gives instant “pre-approved” credit to gig workers based on future wage estimates. The terms are accurate (not deceptive) and users agree voluntarily (maybe avoidable).

- Why it’s abusive: Gig workers cannot protect their own interests because they don’t understand volatility of wage assignment; company takes unreasonable advantage of that structural weakness.

- Why it’s not unfair/deceptive: Clear disclosures, voluntary use.

⚖️ Bottom Line

- FTC/UDAP entities: Safe if they disclose clearly and avoid misrepresentation/harm.

- CFPB/UDAAP entities: Must also avoid exploiting consumer reliance, lack of understanding, or structural inability to protect themselves.

That’s the extra fear factor for those covered by the UDAAP statute: even if you’re not unfair or deceptive, you can still be abusive just for leaning on consumer weakness.

How to know what a consumer weakness is?

This is at the heart of how abusiveness under Dodd-Frank differs from unfairness or deception. The statute itself (12 U.S.C. § 5531(d)(2)) gives three categories of consumer weaknesses that can be unreasonably taken advantage of:

- Lack of understanding – e.g., a consumer does not understand product terms, costs, or risks (think: complex loan structures, add-on products, fine print).

- Inability to protect interests – when the consumer cannot reasonably shop around or negotiate (e.g., urgent small-dollar credit, captive markets1, or consumers with no alternatives2)3.

- Reasonable reliance – when consumers trust a company to act in their interest (e.g., mortgage servicers, debt settlement, or financial advisors making recommendations).

So, a “consumer weakness” is basically any condition that leaves the consumer disadvantaged in evaluating, choosing, or safeguarding their own interests in a transaction.

⚖️ Importantly: Not every disadvantage = abusiveness. The CFPB (when it enforces) typically looks for exploitation of that weakness — not just the weakness itself.

Practical examples of each weakness in consumer lending so you’d see what regulators mean in context?

🔎 1. Lack of Understanding

Consumers don’t fully grasp the terms, risks, or costs.

- Example: Using legalistic or overly technical disclosures that technically comply with TILA but are incomprehensible to an average consumer.

- Example: Failing to clearly explain that the low APR advertised is a base rate and it could vary per customer.

- Example: A lender advertises personal loans as a way to reduce credit card debt but does not clearly explain that the debt is being shifted to a different loan product with distinct terms, such as simple versus compounded interest. While the disclosures are technically accurate, the average consumer may misunderstand the financial implications, creating a potential vulnerability under the abusiveness standard.

👉 Here, abusiveness risk arises because the lender knows the consumer doesn’t understand, but still structures the loan to take advantage of that knowledge gap.

🛡️ 2. Inability to Protect Interests

Consumers cannot reasonably avoid harm due to circumstances.

- Example: A lender offers a loan with an optional credit monitoring service. While enrollment is disclosed and voluntary, cancellation requires the borrower to call during limited business hours and submit written verification. Many consumers fail to complete these steps, resulting in unintentional charges. This creates a practical inability for the borrower to protect their financial interests, which may be considered abusive.

- Example: A lender offers a loan bundled with an optional financial education subscription, such as online budgeting tools or credit coaching. While the subscription is not required to receive the loan and all fees are disclosed, the opt-out process is cumbersome: the borrower must navigate a multi-step online portal, submit written requests within a limited timeframe, or contact multiple departments to cancel. As a result, many consumers end up paying for the service unintentionally, creating a situation where they cannot realistically protect their interests, which could trigger the abusiveness standard under UDAAP.

- Example: A lender markets emergency cash advances to consumers with limited financial literacy who lack access to mainstream credit due to poor credit history, bank account restrictions, or immediate funding needs. Even though online lenders exist, these consumers cannot realistically obtain alternatives quickly enough or qualify for them. As a result, they are effectively unable to protect their financial interests, creating a potential abusiveness concern.

- Example: A lender provides access to an online financial literacy webinar subscription alongside its loans. Although clearly advertised as optional, unsubscribing requires navigating a complex website interface and confirming cancellation through multiple emails. Borrowers who cannot navigate the process remain enrolled, paying for a service they did not intend to use.

- Example: An optional personalized budgeting software is offered with a loan. The software enrollment is technically optional, but opting out involves submitting forms through both the lender and a third-party vendor. Consumers who do not complete every step continue to be billed automatically, demonstrating a situation where consumers cannot realistically avoid or opt out, aligning with the abusiveness standard.

👉 The key is that consumers cannot protect themselves even if they wanted to, so exploitation here is abusive.

🤝 3. Reasonable Reliance

Consumers rely on the company to act in their best interest.

- Example: A lender positions itself as a “trusted financial advisor” but then steers consumers toward high-cost products instead of cheaper alternatives.

- Example: Mortgage servicers misleading borrowers into forbearance4 when modification would be better, because the borrower assumes the servicer is acting in good faith.

- Example: Debt relief companies saying “we’ll help you get out of debt” but enrolling consumers in programs that increase costs.

👉 Here, abusiveness arises from betraying consumer trust that the business fostered.

📌 Bottom line:

- Deception = lying or misleading.

- Unfairness = harm not outweighed by benefits.

- Abusiveness = exploiting consumer weaknesses (lack of understanding, inability to protect, or reliance).

What lenders can do proactively (compliance guardrails) to avoid triggering an abusiveness claim in each of these three areas?

✅ 1. Lack of Understanding

Risk: Borrower doesn’t understand loan terms, risks, or costs.

Guardrails:

- Write disclosures in plain language, not just legalese.

- Give clear examples of how interest accrues, how APR is calculated, and what happens if payments are missed.

- Use comparison tools (e.g., “Here’s what this loan costs vs. another option”).

- Require a customer acknowledgment quiz/check (e.g., “What is your monthly payment? What is the total repayment amount?”).

- Train staff to explain risks consistently, and document consumer confirmations.

✅ 2. Inability to Protect Interests

Risk: Consumer has no realistic way to avoid harm or negotiate terms.

Guardrails:

- Avoid take-it-or-leave-it traps (like forcing ancillary products).

- Offer realistic exit options (reasonable prepayment rights, grace periods, or transparent loss mitigation and refinancing paths).

- Don’t impose barriers to redress, like arbitration opt-out procedures that require certified mailings to waive.

- Audit servicing/collections to prevent unfair repossession or “junk fees.”

✅ 3. Reasonable Reliance

Risk: Consumer assumes you’re acting in their best interest — and you exploit that trust.

Guardrails:

- Never market yourself as a financial advisor unless you actually act in a fiduciary-like capacity.

- If presenting “best options,” actually show the cheapest or most suitable product, not just the most profitable.

- Separate advice from sales — make it clear you are a lender, not a neutral advisor.

- Document consumer acknowledgment of choices (“I was offered Loan A, Loan B, and I chose Loan B because…”).

- Avoid sales scripts that imply trust relationships (“We’ll take care of you,” “We’re on your side”) unless you can back them up.

⚖️ Practical Summary

- Deception → don’t lie or mislead.

- Unfairness → don’t cause net consumer harm.

- Abusiveness → don’t exploit consumer weaknesses.

👉 If you follow these guardrails, you greatly reduce the chance the CFPB or the regulators who can enforce the abusiveness claim will assert you took “unreasonable advantage” of a consumer.

Why the Abusiveness Prong is Particularly Important to Boyledown Lending Inc.

While the abusiveness prong under UDAAP may appear less prescriptive than unfairness or deception, it is conceptually closer to the insights of David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Whereas unfairness and deception focus on measurable harm or misrepresentation, abusiveness addresses situations where lenders may exploit structural power imbalances, consumer vulnerabilities, or limited alternatives — the very dynamics Graeber highlights as socially and morally significant in lending relationships. This alignment underscores why the prong resonates with Boyledown’s values: Debt: The First 5,000 Years heavily influenced the building of Boyledown, guiding the company to design lending practices that are transparent, fair, and empowering, ensuring that debt is a tool for financial opportunity rather than a mechanism for exploitation.

Disclaimer: This blog post is for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide legal, financial, or tax advice. You should consult your own attorney, financial advisor, or tax professional regarding your individual situation and any legal obligations applicable to your business or personal finances.

Email: doboyled@gmail.com

Phone: (631) 379‑0306

Mailing Address:

Boyledown Lending Inc.

285 Crockett Hill Lane

Cross Junction, VA 22625

- Captive Market in Lending

For consumer protection purposes, a captive market in lending arises when borrowers have limited or no practical alternatives to obtain credit, so they are effectively “trapped” into dealing with one lender or a very narrow set of lenders.

Indicators of a Captive Lending Market

Geographic isolation – small towns or rural areas where only one storefront lender operates.

Regulatory barriers – specialized loan types (e.g., payday loans, auto title loans) where only certain licensees are allowed, limiting options.

Borrower profile constraints – consumers with poor or no credit history who are excluded from mainstream credit markets.

Situational captivity – emergencies (medical bills, car repairs) that force borrowers to accept whatever terms are offered.

Institutional settings – e.g., lenders operating around military bases, prisons, or college campuses where borrowers’ mobility or choices are restricted.

Why This Matters for Consumer Protection

Under Dodd-Frank’s abusiveness standard, exploiting a captive market could be seen as taking “unreasonable advantage” of:

a consumer’s lack of understanding of terms,

a consumer’s inability to protect their interests in selecting or using a loan, or

a consumer’s reasonable reliance on the lender to act in their interest.

In a captive market, consumers can’t shop around, so lenders have unusual leverage to impose excessive fees, confusing terms, or aggressive collection tactics without fear of losing business. ↩︎ - A Consumer With No Lending Alternatives

Individual circumstance

This refers to a single consumer’s situation — e.g., someone with bad credit, no collateral, or living in an area with weak banking access.

It’s about personal constraints, not the whole market.

Example:

A consumer has poor credit and can’t get approved anywhere except at one high-cost lender. The market itself might be competitive for others, but this particular borrower is constrained.

👉 In enforcement, this is framed as the consumer’s vulnerability (a weakness the lender could exploit = abusiveness if unreasonable advantage is taken). ↩︎ - 1. A Consumer With No Lending Alternatives

Individual circumstance

This refers to a single consumer’s situation — e.g., someone with bad credit, no collateral, or living in an area with weak banking access.

It’s about personal constraints, not the whole market.

Example:

A consumer has poor credit and can’t get approved anywhere except at one high-cost lender. The market itself might be competitive for others, but this particular borrower is constrained.

👉 In enforcement, this is framed as the consumer’s vulnerability (a weakness the lender could exploit = abusiveness if unreasonable advantage is taken).

2. A Captive Market

Structural circumstance

A captive market exists when an entire consumer group or geography has no realistic alternatives.

It’s about systemic lack of choice.

Example:

A rural town with one licensed small loan company. Everyone in that area who needs short-term credit is effectively “captive” because there’s no competition.

👉 In enforcement, this is about market power and asymmetry — the lender holds leverage over the whole community, not just one consumer.

Why the Difference Matters

No Alternatives (individual):

Lender risk = taking unreasonable advantage of that consumer’s weakness (abusiveness prong #1 or #2).

Captive Market (systemic):

Lender risk = creating/benefiting from a structural power imbalance, where injury is not reasonably avoidable (unfairness) or where reliance is reasonable (abusiveness prong #3). ↩︎ - 1. Forbearance

Definition: A temporary pause or reduction in payments granted by the lender, usually due to the borrower experiencing short-term financial hardship.

Key Points:

The original loan terms remain unchanged (interest rate, principal, maturity).

Usually short-term — e.g., 1–6 months.

Interest may continue to accrue during the forbearance period.

Example: A borrower is behind on payments due to medical bills. The lender agrees to allow them to skip the next two monthly payments without changing the loan term.

2. Modification

Definition: A permanent change to the original loan terms to make repayment more manageable for the borrower.

Key Points:

Can adjust interest rate, principal balance, repayment schedule, or maturity date.

Typically used for long-term restructuring, not short-term relief.

May involve capitalization of unpaid interest or partial forgiveness.

Example: A borrower can’t keep up with a high-interest loan. The lender permanently reduces the interest rate and extends the repayment period, creating lower monthly payments. ↩︎

Leave a comment