THIS CONTENT REFLECTS THE PHILOSOPHY OF BOYLEDOWN LENDING INC., A CONSUMER FINANCE COMPANY LICENSED BY THE VIRGINIA STATE CORPORATION COMMISSION (LICENSE number CFI-256). IT IS INTENDED AS INFORMATIONAL CONTENT AND PROMOTES OUR LENDING MODEL. AS SUCH, IT IS CONSIDERED AN ADVERTISEMENT.

AI Disclosure:

This article was developed with the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) using OpenAI’s ChatGPT. While the ideas and editorial direction reflect the author’s perspective, portions of the research, structuring, and drafting were supported by AI-generated insights. All content was reviewed and finalized by the author.

The UDAP/UDAAP Unfairness Elements

Under federal law, an act or practice toward a consumer is “unfair” if all three of these elements are met:

1. Substantial injury to consumers

- Usually monetary harm (e.g., unexpected fees, lost money, being charged for something you didn’t agree to).

- Can also be reputational harm or significant inconvenience, but purely emotional impact is usually not enough.

- Small individual harms can qualify if they affect a large number of consumers.

2. Injury is not reasonably avoidable by consumers

- The consumer couldn’t reasonably prevent the harm by making an informed choice.

- This often means the terms weren’t clearly disclosed, or the product/service was designed in a way that made it impractical for consumers to avoid the harm.

3. Injury is not outweighed by countervailing benefits

- Any benefits to consumers or competition do not outweigh the harm.

- For example, a fee that causes more harm than the “efficiency” it’s supposed to create would fail this test.

- If the practice is essential to competition and consumer harm is minimal, it might not be “unfair.”

Source references:

- Section 5 of the FTC Act (15 U.S.C. § 45(n))

- CFPB Supervision and Examination Manual, UDAAP Unfairness standards

Not all entities are under the jurisdiction of the Federal Trade Commission, who enforces that statute. Other entities, such as banks and credit Unions, are fall under the jurisdiction of the Consumer Financial Protection Act unfairness statute. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s (CFPB) definition of “unfairness” uses the same three-part test as the FTC, and it’s laid out in 12 U.S.C. § 5531(c).

💡 CFPB nuance:

The CFPB also emphasizes that public policy (such as consumer protection statutes or rules) may be considered when determining unfairness — but public policy alone can’t be the primary basis for finding a violation.

How “Public Policy” fits into the Unfairness Analysis for those Under Dodd-Frank Jurisdiction.

1. What Public Policy Means in an Unfairness Context:

- Public policy refers to:

- Existing laws and regulations

- Established consumer protection principles

- Broad societal goals (e.g., protecting vulnerable consumers, ensuring fair competition)

- It’s not the same as the three core elements of unfairness (substantial injury, not reasonably avoidable, not outweighed by benefits).

2. How It Factors Into Unfairness Analysis

- Public policy can be considered as context or support:

- Example: If another law prohibits a practice, that might signal that the practice is likely to cause substantial consumer injury.

- Example: Consumer protection principles (like transparency or disclosure rules) can help interpret “reasonably avoidable” or “substantial injury.”

- Key limitation: Public policy cannot be the primary basis for declaring something “unfair.”

- You can’t say: “This is against public policy, so it’s unfair,” without also showing that the practice actually meets the statutory unfairness elements.

3. Practical Implications

- Supporting evidence: Public policy references strengthen your argument that a practice is unfair, but they don’t replace the statutory analysis.

- Consistency with other laws: Public policy considerations often overlap with other laws and regulations, providing additional justification for enforcement.

- Analyst guidance: When documenting unfairness, you can cite public policy to reinforce the reasoning, but your primary focus must remain on the three unfairness elements.

✅ Summary:

Think of public policy as a lens or supporting tool. It helps interpret whether a practice injures consumers, is unavoidable, or lacks countervailing benefits, but it can’t be the core reason you call a practice unfair.

Example: A lender charges a hidden fee for processing loan applications. Under UDAAP, you analyze whether this practice is unfair:

- Substantial injury: Consumers are harmed because they pay fees they didn’t expect.

- Not reasonably avoidable: Most consumers cannot detect the fee before submitting the application.

- Not outweighed by benefits: The fee provides no real benefit to consumers.

Public policy context: Existing state laws require lenders to disclose all fees upfront. While this law reflects public policy promoting transparency, the unfairness determination does not rely solely on that law. Instead, the law supports the analysis by showing that hidden fees are contrary to established consumer protection principles, reinforcing the conclusion that the practice causes substantial injury and is not reasonably avoidable.

In short: public policy strengthens the argument, but the legal elements drive the decision.

Is saying that something violates public policy the same as saying that something violates the law?

Not exactly.

1. Law

- Formal, codified rules enforced by governments: statutes, regulations, or court decisions.

- Example: “Lenders must disclose all fees upfront” is a law.

2. Public Policy

- Broader concept encompassing goals, principles, or societal values that laws are meant to advance.

- Can be reflected in laws, regulations, or government guidance, but also includes unwritten principles of fairness or consumer protection.

- Example: Protecting vulnerable consumers or ensuring transparency in financial transactions is public policy—even if no single law spells it out exactly.

3. Key Takeaway

- All laws reflect public policy, but not all public policy is codified as law.

- In UDAAP analysis, public policy is used as supporting context, often pointing to existing laws or principles, but it cannot replace the statutory elements of unfairness.

Here’s an example of how public policy would be cited without a clear cite to a formal law

Example: A payday lender markets extremely high-interest short-term loans to financially vulnerable communities, emphasizing quick cash but downplaying long-term costs.

Unfairness analysis under UDAAP:

- Substantial injury: Borrowers face high fees and a cycle of debt.

- Not reasonably avoidable: Many consumers lack the resources or knowledge to fully understand the costs.

- Not outweighed by benefits: Quick access to small cash sums is outweighed by long-term harm.

Public policy citation (without a formal law):

- The CFPB might note that “consumer financial practices that exploit short-term financial needs of vulnerable populations are inconsistent with widely recognized principles of consumer protection and responsible lending.”

- Here, no specific statute is cited, but the argument relies on general societal and regulatory principles—the idea that taking advantage of vulnerable consumers is against public policy.

✅ Key point: Public policy can provide contextual or persuasive support to show why a practice is harmful or contrary to consumer protection norms, even if there isn’t a specific law explicitly prohibiting it.

Here are three more concise examples of how public policy might be cited without referencing a formal law:

1. Misleading marketing to seniors

- A financial product is advertised with promises of “guaranteed retirement income,” but the risks are not disclosed.

- Public policy note: “Practices that mislead older consumers about the security of their retirement savings are contrary to widely accepted principles of consumer protection and financial transparency.”

2. Aggressive debt collection

- A company repeatedly calls consumers at all hours, using intimidating language to demand payment.

- Public policy note: “Industry standards and consumer protection norms recognize that harassment in debt collection undermines fair treatment of consumers and is inconsistent with responsible lending practices.”

3. Hidden service fees

- An app charges small, frequent fees that are difficult for users to detect.

- Public policy note: “Transparent pricing and disclosure are fundamental principles in consumer financial protection, and practices designed to obscure fees conflict with these principles.”

In each case:

- No formal statute is directly cited.

- Public policy is used to frame the analysis, showing that the practice violates recognized principles, supporting the unfairness determination.

A Mnemonic to remember the Unfairness Elements?

UCOSINANBOBB

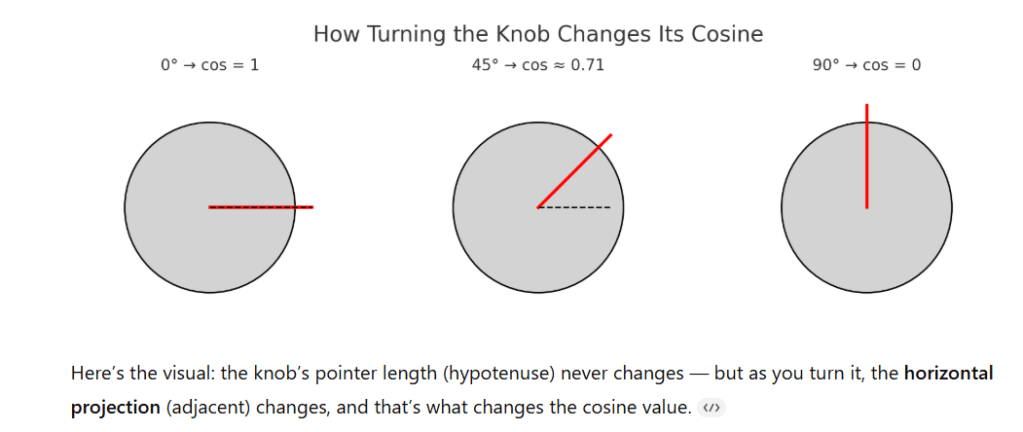

Say it like “U COSINE A KNOB.”

To establish unfairness, UCOSINANOBB.

U-Unfairness [is when the]

C-cause

O- of

S- substantial

I- injury [is]

N- not

A- avoidable [and]

N- not

O- outweighed (by the)

B- benefits (to the consumer)

UCOSINANOB. Maybe not the best mnemonic. But it’s useful to me in the short term. And that it really where mnemonics are at their best. They are at their worst in long term learning. So why learn it? Well, it got me to understand cosine more than I ever have. Before trying to figure out this mnemonic I could never have answer this question: ‘what is the cosine of a knob’.

Now I can say, fairly confidently, that the cosine of a knob depends on how far you twist it. This is because twisting the knob alters the adjacent side of the angle of the knob. That is to say, the side of the angle that is not the hypotenuse. See the above picture for reference.

I know, this all seems like it has nothing to do with learning the UDAP/UDAAP unfairness elements. It seems like this article has failed beyond making me a wannabe mathematician.

Wrong. What I’ve done here is START with mnemonics. But where I arrived was somewhere a lot more complicated than that with respect to memory recall. I don’t know about unfairness solely because I memorized UCOSINANOB. I know it because after I started there, I made interconnections to other topics that I find interesting. The glue is not in the mnemonic itself. It is in the byproduct of working to validate the accuracy of the mnemonic I made that will make me remember the unfairness elements. Not the mnemonic itself.

The mnemonic I made for DECEPTION: Deploy robots on puffy low maintenance mushrooms is successful for the same reason. I don’t remember that the mnemonic means ‘Deception is when representations, omissions or practices [are] likely [to] mislead [consumers] materially because I strung the words together. I remember it because after I strung the words together I created an animated video to visualize the sensibility of the phrase.

Why Consumer Benefit from Knowing the “Unfairness” Elements

For consumers, understanding these prongs is more than legal trivia — it’s a practical tool.

- You can spot harmful practices early, before they drain your wallet or limit your choices.

- You can speak regulators’ language when filing complaints, making your case harder to dismiss.

- You can push back on misleading defenses, such as claims that something “helps competition,” when the harm clearly outweighs any benefit.

- And importantly, it can help the company you’re complaining to understand exactly where the problem lies, so they can address and remedy it themselves without waiting for regulators.

Knowing these three points turns a vague feeling of “this seems wrong” into a documented legal argument that can be acted on by regulators, advocacy groups, or courts.

Disclaimer: This blog post is for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide legal, financial, or tax advice. You should consult your own attorney, financial advisor, or tax professional regarding your individual situation and any legal obligations applicable to your business or personal finances.

Email: doboyled@gmail.com

Phone: (631) 379‑0306

Mailing Address:

Boyledown Lending Inc.

285 Crockett Hill Lane

Cross Junction, VA 22625

Leave a comment